Check Casher Proliferation Bill

(S.3237 Sepulveda / A.480 Cruz)

Purpose: This legislation allows check-cashers to cash checks valued at up to $20,000 and cash post-dated checks. It also permits check-cashers to advertise their services electronically.

Background: The check-cashing industry emerged from the banking crisis of the Great Depression and has been regulated by New York since the Check Cashers Act of 1944. Although customers typically cash checks with banks and credit unions for free, check-cashers offer those services to anybody for a fee. Ace Cash Express’ 2006 SEC report summarizes the industry eloquently:

“We operate in the check cashing and short-term consumer loan industries. Growth in these industries has been fueled by several demographic and socioeconomic trends, including an overall increase in the population and declining to stagnant growth in household income of lower- and middle-income people. [...] Closings of less profitable or lower traffic bank branches, primarily in lower-income neighborhoods where the branches have failed to attract a sufficient base of customer deposits, have resulted in fewer convenient alternatives for consumers. These trends have combined to increase demand for the basic financial services we provide.”

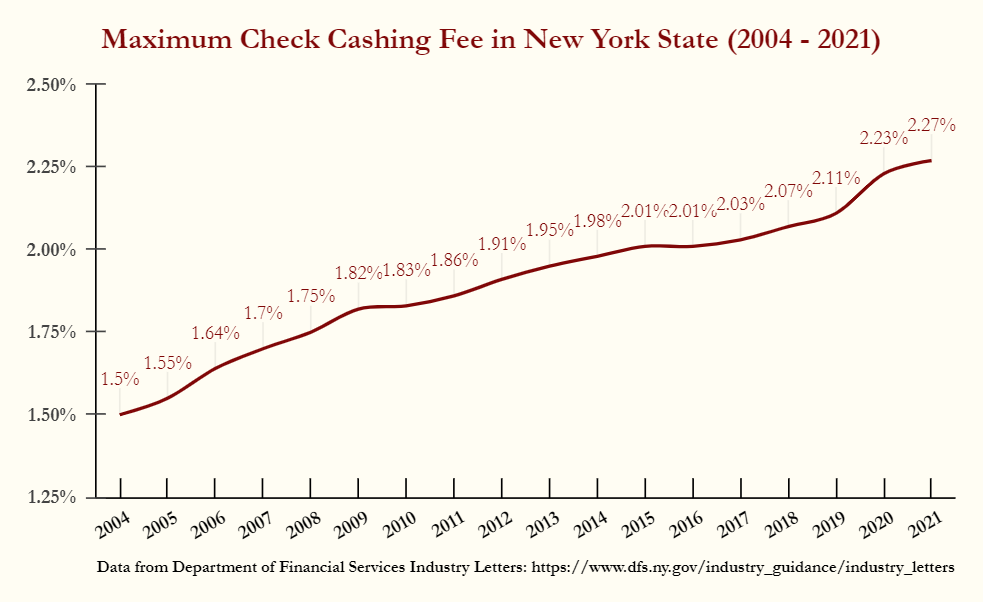

The check-cashing industry in New York has grown dramatically in recent history due in large part to dramatic deregulation. In 1988, the maximum rate for check-cashing was raised from 0.75% to 0.9%. The most dramatic deregulations for the industry occurred very recently: between 2004 and 2021.

Justification: Check-cashers extract profits from financial precarity. Like cryptocurrency exchanges, payday lenders, pawnshops, and other similar enterprises operating at the margins of our banking system, check-cashers often use provocative language when discussing the laws that govern their behavior: loosening regulations empowers them to take on Wall Street, while tightening regulations means the most vulnerable among us suffer.

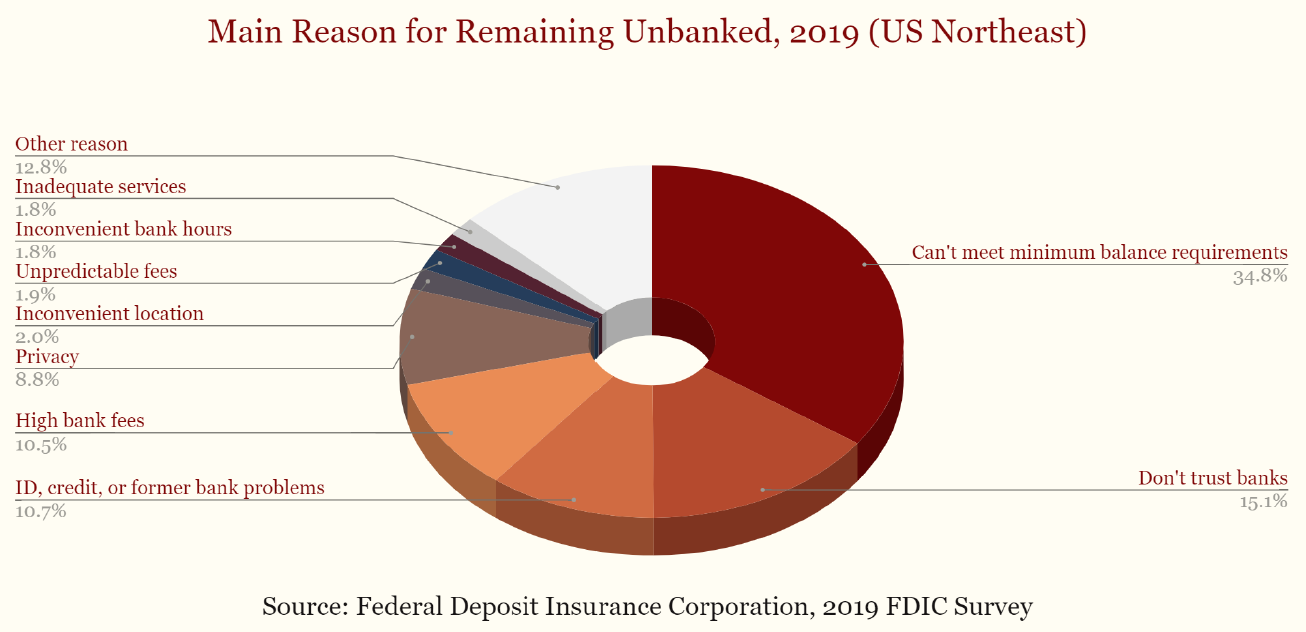

In limited circumstances, check-cashers do, unfortunately, play a critical role for many of the 411,000 (5.6%) New York households who do not have bank accounts due in large part to their inability to meet minimum balance requirements along with skepticism about their practices, privacy concerns, unpredictable fees.

However, rather than fortifying the roles of inherently predatory businesses by loosening the rules, we encourage state legislators to instead devote their energy toward a positive vision of universal financial services centered around well-regulated credit unions and banks. If decades-old regulations protecting the working class pose an existential threat to a business model, we consider that business model to be very unfortunate.

TIMBER nurtures daily democracy in the Capital Region by advocating for reforms to make our civic infrastructure more resilient, effective, and accountable. We strongly oppose this legislation.