New York Public Banking Act

(S.1754 Sanders/A.3352 Hunter)

Purpose: This legislation introduces a framework to allow local governments to establish public banks.

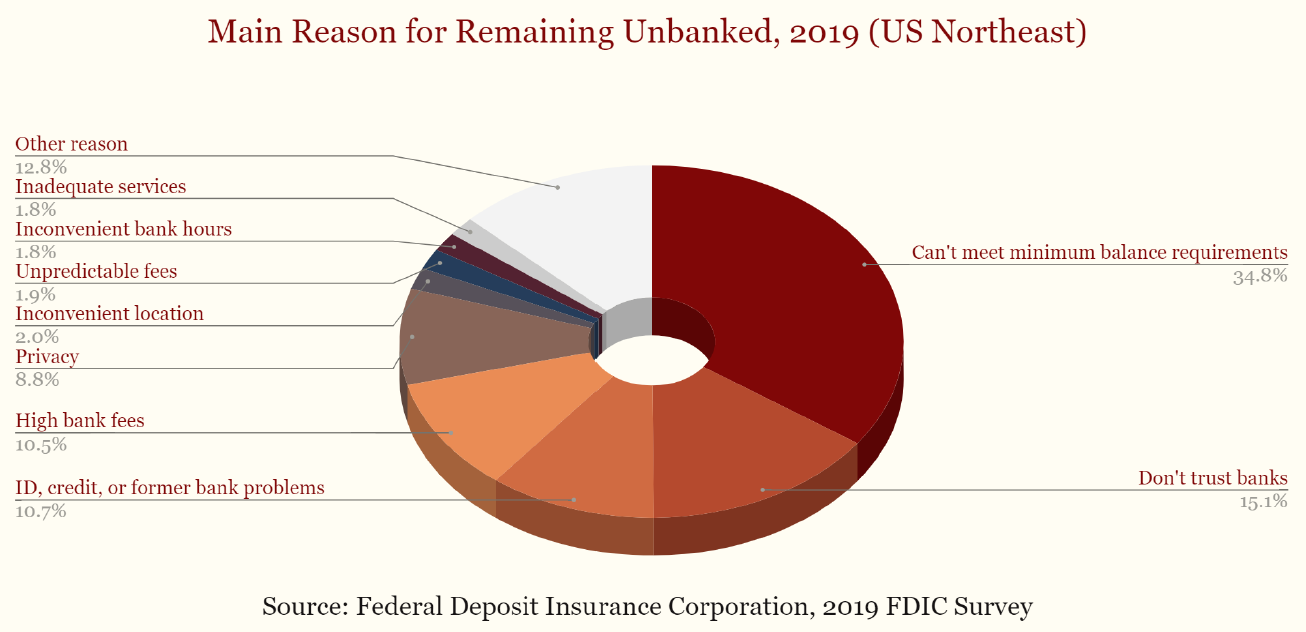

Background: While retail banking has always played a crucial role in personal finance, the uneven distribution of stimulus money and a sharp rise in paychecks distributed by direct deposit (94%) have recently elevated its importance for ordinary Americans. Unfortunately, a 2019 FDIC survey found that 411 thousand (5.6%) New York households do not have bank accounts. Of the Northeastern respondents, only 1.8% shared that banks don’t offer their preferred services, whereas a plurality found the standard minimum balance requirements to be financially prohibitive for them. Among the remaining respondents, most refrain from personal banking due to mistrust of banks, privacy concerns, and the unpredictability of fees. There are 4,839 FDIC-insured banks in the United States, and these New Yorkers – over 100 thousand households in all – mistrust all of them.

It is reasonable that the financially precarious might harbor skepticism about giving their money to banks that habitually find ways to keep it. Between 1998 and 2020, just 6 major US banks paid $195 billion in sanctions and settlements in 395 major legal actions over practices like predatory lending, price-fixing, misuse of customers’ cash, overcharging, misuse of client order information, debt collection abuses, and undisclosed billing. Private financial institutions routinely behave this way because they have a fiduciary responsibility to act in their shareholders’ – not their clients’, or society’s – best interests.

Public banks are attractive alternatives for the many New Yorkers who cannot, will not, or should not bank with private financial institutions. Because they are governed accountably and democratically, they provide services of genuine value even if they are not individually lucrative.

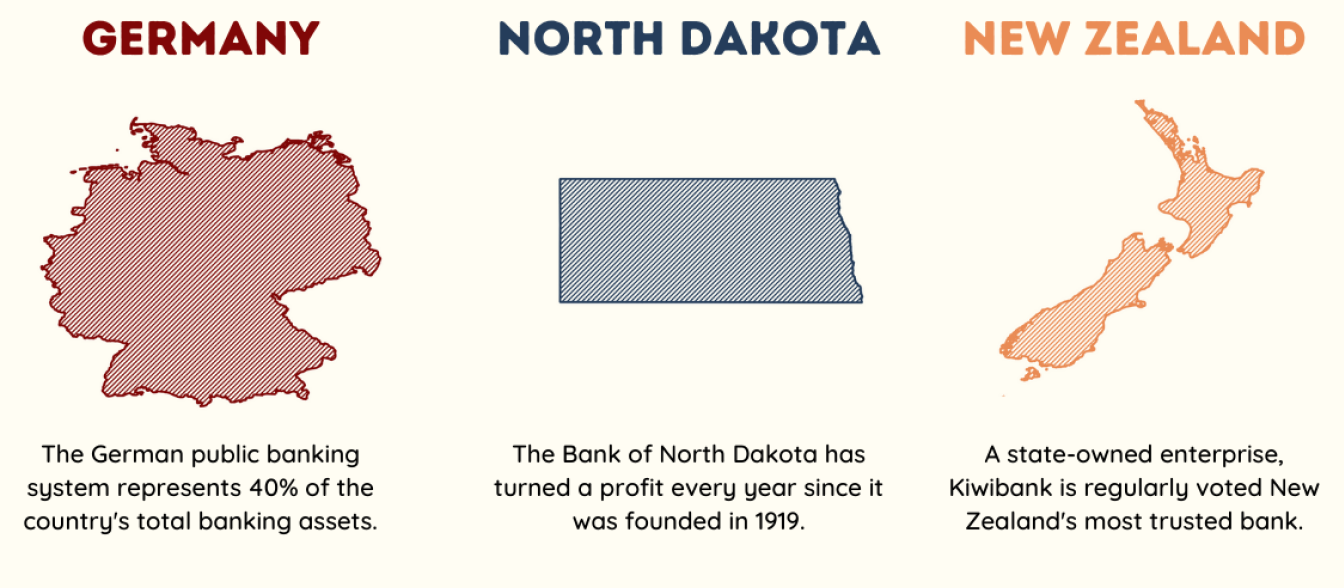

The benefits of legitimate accountability go well beyond retail banking. Public banks have a structural incentive to finance large-scale projects that address problems in the real world, like mass transit or renewable energy. Investment in inherently valuable projects rather than spreadsheet abstractions also has a stabilizing effect on the region during economic downturns, as demonstrated by the Bank of North Dakota’s performance during the Great Recession and again during the coronavirus pandemic. In Troy, a clear use case for this framework would be the establishment of a local infrastructure bank tasked with financing improvements to our water system, service lines, and roadways.

By partnering public institutions that can finance projects with public authorities that can implement them, public banking allows local governments to pursue their mandates faithfully. Without that funding, many counties and municipalities pass laws with no way to meaningfully enforce them. These dead laws are undemocratic, and they have a chilling effect on future civic engagement.

Justification: TIMBER advocates for enhanced citizen involvement in the parts of democracy that happen between elections. As taxpayers, we already subsidize the banks operating in this state. A democratic society should ensure that we should have a say in how that money gets used.

TIMBER nurtures daily democracy in the Capital Region by advocating for reforms to make our civic infrastructure more resilient, effective, and accountable. We fully support this legislation.